Chapter 13 - Salmon Feasts and Cold Water

First impressions of Bella Bella, British Columbia

Previous chapter / Next chapter / Start at the beginning

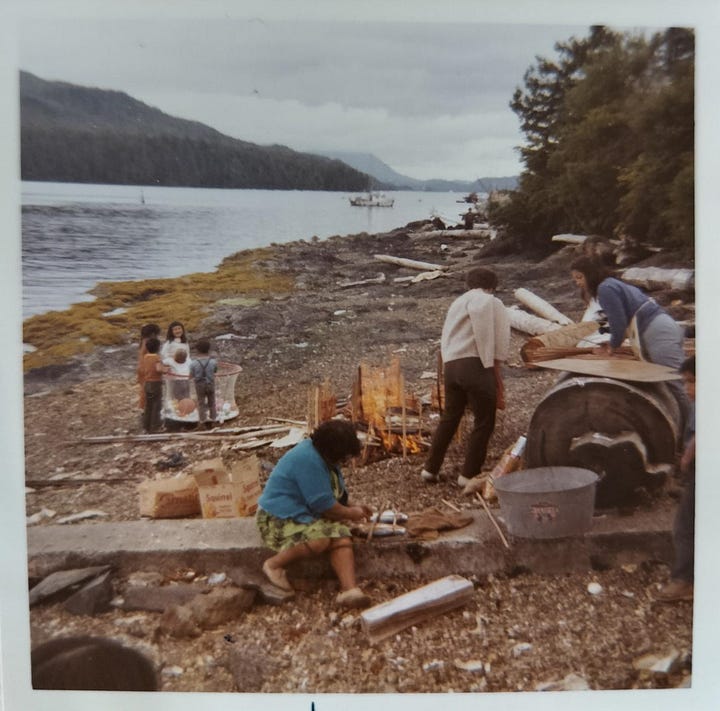

When Trish arrived in Bella Bella the second week of September 1970, it was still fishing season. The local men left the village daily on their fish boats to fish the salmon that would feed their families through the winter. In Bella Bella, where the residents preserved fish for personal consumption, using traditional Native practices, they barbecued the fish over an open fire, then canned it. They cleaned each fish, splayed it so it lay flat, then wove the thin flexible ends willow boughs around some of the fish, like a cage, to hold them open, leaving the stronger ends of the boughs as a handle. When they were done, the strong ends of the willow were dug into the small rocks of the beach, until the fish stood around each of the fires, looking a bit like circles of oddly shaped tennis rackets, ready to be barbecued. Other’s used larger sticks to hold several fish open and standing around a fire at a time. The fires crackled, and the aroma of fresh fish cooking wafted through the village. People gathered and enjoyed a meal on the beach around the fires. They invited Trish and the other hospital staff to join in for the open-air feast of salmon, seaweed, and fish eggs. The barbecued fish tasted as good as it smelled.

Eager to be useful, Trish shared the work in bringing wood to keep the fire burning on the beach. Driftwood, carried in on the tide and deposited beyond the high tide line was dry enough to burn. Trish clambered over large boulders and rocks searching for a good log to bring back to the fire. After finding a suitable one, she hoisted it onto her shoulder and began retracing her path back to the beach. At one point, she placed a hand on a boulder to steady herself. Suddenly, the log slipped from her shoulder and landed squarely on her fingers, which were outstretched on the rock. It rolled off moments later. Inspecting her hand, Trish noticed her fingers looked pale and flattened, like dough rolled with a rolling pin. Strangely, she felt little pain, despite the impact. She shrugged it off and carried on enjoying the evening on the beach.

By the time the feast was done, Trish’s fingers were swollen and painful. After returning to the nurses’ residence, she went to see Dr. Henderson. She showed him her hand. He prepared a bowl of ice water, plunged her hand into it. The pain cut through her like a knife. He held her hand in the ice water for what seemed like a lifetime, then gave her an analgesic and sent her to get some rest. The next morning Trish woke up to find her fingers swollen to the point of being shiny, with the middle one in particularly throbbing unbearably. Each pulse brought such intense pain that she feared the finger might burst.

She again showed her injury to Dr. Henderson, who took her into a treatment room. He heated a needle in the flame from a Bunsen burner and used it to pierce the nail on her middle finger. The moment he did, a jet of fluid shot up to the ceiling. The pain was excruciating, then, some relief. Satisfied with the outcome, Dr. Henderson wrapped her fingers. Trish carried on with her day and worked her shift.

That incident occurred during her first week in Bella Bella, and Trish took it as a sign of what life there would be like. She realized she needed to stay alert and agile in the rugged environment. Life was simple, but it was also raw, with more hazards around.

The small hospital was the only immediate resource, and outside help was far away. Bella Bella sat on the rocky shoreline of Campbell Island, some 400 miles north of Vancouver. In cases of serious illness or accidents, patients had to be flown to the large hospitals in Vancouver. Because of their isolation, the people who lived in the village had practical, often traditional solutions for challenges they faced.

In Bella Bella, the daily work of nursing felt more familiar to Trish than it had over the summer in Namu. She now lived in the nurses’ residence alongside other hospital staff. The two-story building was just across a boardwalk from the hospital.

The Matron of the small hospital, like Trish, was an English-trained nurse. Although the two other nurses were Canadian-trained, the Matron ran the hospital according to English nursing practices. Day shifts had two nurses and one nurses’ aide on duty, night shifts had one nurse and one aide. The aides were local women, Native residents of Bella Bella.

The Matron organized the schedule, which covered two 12-hour shifts per day. As employees of the United Church, the staff began their mornings with a brief church service before starting their hospital shifts. A small pump organ, requiring a child to crawl under the organ to pump air into the harmonium, sat in the main floor hallway, added a formal touch to the services. The hospital secretary played the organ on most mornings, and the staff joined in to sing. Dr. Henderson gave a short sermon, before the staff set about the work of the day.

The R. W. Large Memorial Hospital, newly built in 1902, was not well-designed for its purpose. The two-story building had its wards upstairs with about 12 beds, while the treatment rooms and the nursery were downstairs. There was no elevator. The stairs, comprising eight steps, a landing, then another eight steps, posed a challenge to the movement of people and equipment within the hospital.

When patients were admitted to hospital and couldn’t climb the stairs, staff had to carry them up to the wards. The village had an ambulance, but it also doubled as a delivery van, transporting supplies from the dock to the store, the hospital, and other locations. If a patient that needed to be carried upstairs in the hospital, the ambulance would be called. The nurses, the aide, and the van driver worked together to carry the patient up the stairs.

Nursing in Bella Bella was like nursing anywhere else, though the services were basic because of limited diagnostic tools. Dr. Henderson sent serious cases to larger cities where there were hospitals with more services, but there weren’t many seriously ill or injured patients.

Daily work included managing new admissions, making beds, providing personal care for in-patients, administering medications, cleaning and dressing wounds, and assisting Dr. Henderson during minor procedures and general surgeries. Dr. Henderson, a generalist physician, managed anesthesia and general surgeries. He was six or seven years older than Trish and had been working at the hospital for several years.

In both Bella Bella and Namu, Trish was an employee of the United Church of Canada. The church had a local presence in Bella Bella, with the pastor and the hospital staff all working as church employees. A Board of Directors, which included the pastor and the hospital administrator oversaw the local United Church and the hospital. They worked with the local band office and the provincial and federal governments on such matters as receiving and distributing government funds to the band office.

Bella Bella was home to two churches: The United Church, and the Pentecostal Church, on opposite ends of the village. Unlike the United Church, the Pentecostal church had a zero-alcohol policy for its members, but it had a well-known brass band that people wanted to be part of. In the past, the Bella Bella Brass Band was renowned across the province for its talent, winning competitions and earning respect. While the United Church didn’t have a band, they had a choir. Music was a vital part of the community.

Bella Bella was also known for its talented traditional artisans. Women and children created intricate beaded jewelry, bags, and decorations, while other artists crafted silver jewelry, wood carvings, and paintings. During her time there, Trish acquired several handmade pieces-some bought, others gifted, that she cherished through the years.

In November, two months after Trish arrived in Bella Bella, she and another nurse, Lorna, had a day off together. Lorna, a recent graduate of the University of Victoria nursing program, had also just started working in Bella Bella. The weather was beautiful—cool air and brilliant sunshine-so they decided to spend the day canoeing on the saltchuck.

By the afternoon, they had paddled nearly a mile up the channel, following the shoreline and chatting all morning. They noticed a tugboat approaching but thought little of it, assuming it would follow the speed limit designed to prevent wash from damaging wharfs and structures.

The tugboat, however, was moving much faster than expected. It was large, towing two barges, and created a massive wake. The women pivoted their canoe into the first wave of wash, holding it steady. They struggled, but held the canoe in position for the second wave, but the third wave struck harder. It turned them broadside, and the canoe capsized, the women thrown into the churn of the wash.

Trish felt the frigid cold of the Pacific Ocean pierce her as the water closed over her head. Disoriented, she surfaced, thrashing to grab something—anything. Neither woman had worn a lifejacket, the calm, protected water of the channel hadn’t seemed dangerous earlier.

Trish could hear Lorna screaming her name, but her voice sounded far away. Realizing she had surfaced underneath the overturned canoe, Trish hesitated. She had air, and as she clung to the beam of the overturned canoe, she felt safer, knowing she couldn’t swim. But Lorna, unable to see her, was panicking, thinking Trish hadn’t resurfaced. Hearing Lorna’s frantic calls, Trish knew she had to act.

Ducking back under the water, she pushed herself out from under the canoe, and surfaced where Lorna could see her. Gasping for air, she groped for the canoe’s gunnel with numb hands. Lorna was there and the two women clung to the overturned canoe. They tried to right it but couldn’t manage in the freezing water. Exhausted, they held on; it was so very cold.

The women watched as the tugboat continued on its course, its operator oblivious to their situation. The gravity of their predicament sank in. Trish knew the fishing season was over, and the fishboats were tied up and unmanned. Boat traffic in the channel was sparse this time of year. They considered trying to paddle their way to the nearest bank, but then what? Wet and cold in the chilly air, they’d likely succumb to hypothermia quickly. Their situation looked bleak.

Amid the sound of waves slapping against the overturned canoe, Trish thought she heard a boat engine. She and Lorna repositioned themselves to look toward the village. Sure enough, a fishboat was rumbling toward them. Help was coming, they just had to hang on. The large boat carefully pulled up alongside the overturned canoe. The captain leaned over the side, used a boat hook to catch Lorna by the waist of her pants and in one swift motion, hauled her onto the deck. Trish felt a sudden pull around her waist, and in an instant, she too sprawled in a heap on the deck beside Lorna.

Their rescuer was angry. He didn’t speak to them as he turned the boat and started back toward the wharf, but his anger was clear. Trish was well aware of his obvious disgust of the situation they had put themselves in, but she was so cold, and so relieved to be out of the water, she simply lay in a grateful heap on the deck.

At the wharf, a small group of people was waiting. They took the women straight to the nurses' residence, where Dr. Henderson quickly assessed them. Confirming Trish and Lorna were uninjured; he instructed the off-duty nurses who had gathered to put the hypothermic women in warm baths, clothes and all. The residence had two bathrooms, each with a bathtub-one upstairs and one downstairs. Their colleagues settled Lorna into one warm bath, and Trish in the other. Slowly, the water thawed their frozen bodies.

Trish was beginning to feel human again when she heard Lorna shout up from the bathroom below:

“Trish, are you still chewing your gum?”

Trish laughed out loud—she was. Both women had popped in a stick of gum shortly before their canoe capsized. Despite their ordeal, they had somehow kept chewing, even through teeth chattering with hypothermia.

That day taught Trish many important lessons. She became much more cautious around water, and on boats. She and Lorna realized just how lucky they had been. Someone in the hospital had seen them capsize and put out a “mayday” call over the hospital’s radio. The fisherman who rescued them just happened to be on his fishboat, with the radio turned on. He later said he didn’t know why he turned his radio on, there was no reason to do so. If even one link in that chain of events had been missing, the outcome could have been tragic.

Once the women were warm and dry, they received plenty of stern lectures about water safety, especially about wearing lifejackets. The police boat from Ocean Falls showed up the next day. The officer made sure Trish and Lorna clearly understood how stupid they had been, as did anyone else from miles around who had access to a radio. As for the tugboat operator who was speeding, there were no consequences. The vessel, registered in the United States, had already left the area by the time the police boat arrived in Bella Bella.

A few days later, on Remembrance Day, their colleagues and others in the village joked that Trish and Lorna celebrated their own “Remembrance Day” three days earlier, when they nearly became a memory themselves.

As November turned to December, the village became a hive of Christmas related activities. For Trish, this would be her first Canadian Christmas, and she missed her family more than usual. She wondered what Christmas would be like in such a remote location, but she wouldn’t have to wonder for long.

The choir at the United Church started rehearsing Handel’s Messiah, a huge undertaking. The idea was so exciting, a few of the nurses joined in. However, after a couple of practices they were asked to leave. Their soprano voices didn’t blend well with the deeper voices in the choir or suit the overall arrangement of the piece as it was being rehearsed. Trish agreed with the assessment so she and the others stopped going to the practices, but eagerly looked forward to the Christmas performance.

People in Bella Bella did their Christmas shopping through catalogues, and many had already placed orders for gifts and special food. Catalog orders arrived by boat, on a once-a-week schedule. On delivery days, most of the village gathered at the wharf to await their packages. To Trish, each delivery day felt like a connection with the outside world, making it a special occasion.

The nurses decorated both the hospital and the nurses’ residence, and Dr. Henderson dressed up as Santa, handing out gifts in both locations. Most patients went home for Christmas, and family visited those who stayed, treating them to good food, helping them enjoy the holiday as much as their circumstances allowed.

The Christmas service at the United Church was unforgettable. The choir, having practiced diligently, gave a stunning performance of Handel’s Messiah that added a special touch to the season.

Previous chapter / Next chapter / Start at the beginning

If you are enjoying reading Trish’s story, please consider supporting my work by buying me a coffee.

Coffee makes the world go round, and the words flow, as they say!

Author’s Notes

N.B.1: In 1970, as Trish was introduced to the people of Namu, Bella Bella, and other communities where she worked, the language of the time, “Natives”, was used. Today, the people living on the lands where Trish worked, have reclaimed their traditional identities, leaving behind the nomenclature assigned them during colonization.

Namu and Bella Bella sit on the traditional territories of the Heiltsuk Nation. If you would like to read more about the identity and culture of First Nations people in Canada, including insights from Indigenous authors and advisors, here is a resource from the “First Nations & Indigenous Studies” program at the University of British Columbia.

N.B.2: We often see our parents through the lens of their roles in our lives— caregivers, disciplinarians, cheerleaders. Perhaps they are our role models or mentors, but who were they before they became these things to us?"

To better understand who my parents were before they were, well, my parents, I set about interviewing them about their lives before marriage and kids. I started with my mom.

Trish Lewis was 18 years old and desperate to escape a mind-numbing administrative job at a factory in Liverpool in the 1950’s. She made the impulsive decision to join a friend to interview for nurse’s aide training at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital. That decision changed the trajectory of her life and launched her into an interesting and rewarding career as a nurse.

Trish is my mom, and this is her story, as told to me in a series of interviews in 2024. The story is pieced together from Mom’s memory, photos, and documents. As we all know, memory is fallible. In the telling of this story, some names have been changed, either because they could not be recalled, or to protect the privacy of the person. The Journey is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

N.B.3: If you are enjoying this story, you may also enjoy reading my memoir, “Resilience in the Rubble: A True Tale of Aid and Survival in Kashmir”. The book shares my experience as a first-time medical aid worker in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan, after an earthquake devastated the region in 2005. It also tells the story of Nadeem Malik, a local teenager who lived through the earthquake, and his struggle to provide for his family in the aftermath.

Norwegian salmon 🍣 is the worst thing you can w

eat ..